Background

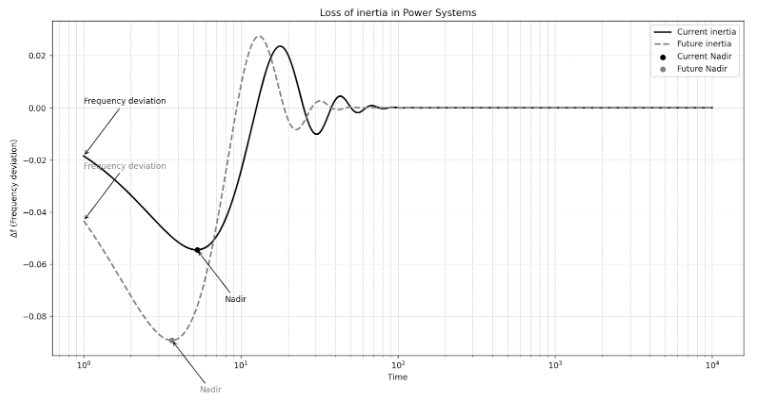

In the past years, there has been a rapid deployment of renewable energies worldwide, driven by international goals to reduce CO2 emissions. The faster these new installations are implemented, the more challenging it becomes for the system to adapt. However, this presents an opportunity to innovate and improve its adaptability to this new type of generation. The resulting issues include challenges such as inertia, power ramps, voltage instability, and frequency instability. Figure 1 illustrates an example of how the key indicators of a bulk power system’s health could be affected by the loss of inertia. It shows that the frequency nadir is lower, and the Rate of Change of Frequency (RoCoF) is higher in a power system with less inertia.

The literature presents numerous studies aimed at addressing these challenges, which arise from the increased use of Inverter-Based Resources (IBR). Among the proposed solutions, droop response and inertia emulation have been identified as the most effective algorithms to mitigate stability issues. However, the sheer volume of proposed control strategies for converters can overwhelm the industry. To ensure effective coordination, it is essential to strike a balance between cutting-edge proposals and practical industry needs.

Figure 1. Comparison of frequency deviation under loss of inertia

Grid Following Converters (GFL) as Part of the Solution

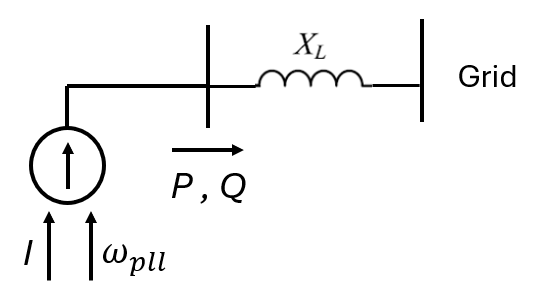

The majority of IBRs are based on the Grid-Following (GFL) topology, which means they require an external grid to operate. As their name suggests, GFL converters follow the external voltage waveform and frequency. A key component of this topology is the Phase-Locked Loop (PLL), which ensures continuous synchronization of the converter with the grid by frequently sampling the voltage spatial vector (typically using Clarke and Park transformations). A typical simplified model for this kind of topology is a current source behind a series impedance, as depicted in Figure 2.

This feature allows GFL IBRs to have a very fast response, offering significant advantages over traditional generation. One notable benefit is their rapid response at the converter point of interconnection (less than one cycle). For this reason, GFL converters can “emulate” instantaneous phenomena such as inertial response to help reduce the ROCOF, mimicking the swing equation of traditional synchronous machines while providing a fast primary frequency response (droop response). [1]

However, there are limitations to using GFL technology for frequency support, including:

Figure 2. Simplified model of GFL-based inverters.

Grid Forming Converters (GFM) as a solution

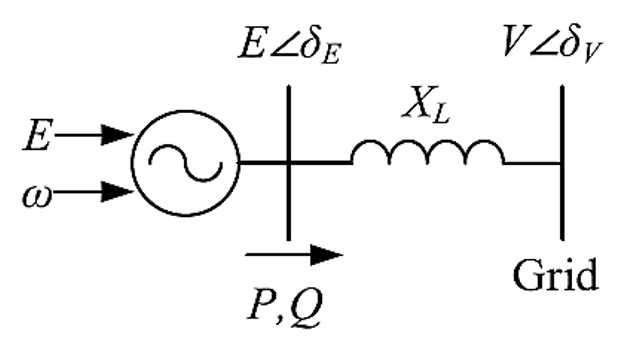

To address the shortcomings of GFL technology, Grid-Forming (GFM) converters have been introduced in both literature and industry. Unlike GFL, GFM IBRs can operate independently of the grid and can, for instance, provide black start services. This capability allows GFM technology to form voltage waveforms without external support, eliminating the need for a PLL and offering advantages over GFL converters. The simplified model of a GFM inverter is depicted in Figure 3. It is an ideal voltage source behind a series impedance.

GFM technology creates a Virtual Synchronous Rotor that emulates angular speed affected by generation-load mismatches. This virtual angular speed determines the instantaneous angle of the spatial vector, enabling operation in instantaneous spaces (Park or Clarke transformations). [2] [3]

Figure 3. Simplified model of GFM-based inverters.

Real inertia of GFM IBRs (Non-Emulated)

The nature of inertia lies in energy storage elements. For mechanical systems, inertia is stored as kinetic energy, with speed as the state variable representing its level. Similarly, electrical systems store energy in inductors or capacitors, in the form of magnetic or electric fields.

In renewable energy systems, inverters often employ a back-to-back configuration with a capacitor in the DC link between the resource and the IGBT bridge. This DC capacitor stores energy, with voltage as its state variable. Without a frequency support algorithm, converters can naturally deliver their inherent inertia to the grid via their DC link capacitors.

This opens opportunities to enhance real inertia by integrating supercapacitors into the DC link, bypassing the need for emulated inertia from battery energy storage systems (BESS) based on GFM technology. While promising, this approach is still in the research stage and may take years to reach industry adoption.

Regulations and Trends

Due to the large number of proposals for control loops of GFM converters, the industry aims to standardize the interconnection requirements for inverter-based generation technologies. Additionally, organizations such as WECC propose standardized models to be used not only in the industry but also in academic studies.

WECC Models: The Western Electricity Coordinating Council has published two models to standardize GFM control loops:

Centralized vs. Decentralized Inertia: Challenges and Future Prospects

Ongoing research explores centralized and decentralized inertia approaches (provided by a power plant controller or locally at each inverter, respectively). This raises key questions for the future:

This solution mimics the behavior of conventional synchronous machines. This response is a spontaneous local response at the inverter level and has no specific objective at the POI. Unlike synchronous machine-based generation plants, converter-based plants require a significantly larger number of generation units to achieve the same nominal power at the POI and an internal network to evacuate the power from the generation units to this point. This difference means that decentralised inertial response alone is an option, but not sufficient to coordinate an effective inertial response at the POI.

This option is challenging given the current delays in the response at the POI of renewable plants. However, a centralised inertia emulation by a Power Plant Controller (PPC) would allow a coordinated response to the frequency measured at the POI. In this topology, the PPC sends power references to each inverter in the plant, eliminating the need for major changes to inverter control to provide local inertial response. Future advances in communications technology would allow the plant response to be faster and, enabling PPCs to provide more accurate and faster centralised inertial responses at the POI.

The local inertial response could act within shorter time windows, leveraging the faster response of this configuration, while the centralised response can coordinate each inverter over a longer time window to ensure the desired response at the POI. This approach could provide a fast and coordinated inertial response at the POI level, complying with future grid code requirements. Research into the combined response of centralised and decentralised control topologies is key in this context.

[1] Remus Teodorescu; Marco Liserre; Pedro Rodriguez, «Grid Converter Control for WTS,» in Grid Converters for Photovoltaic and Wind Power Systems , IEEE, 2007, pp.205-236, doi: 10.1002/9780470667057.ch9.

[2] W. Du, Z. Chen, K. P. Schneider, R. H. Lasseter, S. Pushpak, F. K. Tuffner, and S. Kundu, “A comparative study of two widely used grid forming droop controls on microgrid small signal stability,” pp. 1–1.

[3] W. Du et al., «A Comparative Study of Two Widely Used Grid-Forming Droop Controls on Microgrid Small-Signal Stability,» in IEEE Journal of Emerging and Selected Topics in Power Electronics, vol. 8, no. 2, pp. 963-975, June 2020, doi: 10.1109/JESTPE.2019.2942491.

keywords: {Voltage control;Inverters;Microgrids;Power system stability;Stability analysis;Low pass filters;Frequency control;Droop control;grid-forming;inverter;microgrid;stability},

[4] R. W. Kenyon, A. Sajadi, A. Hoke and B. -M. Hodge, «Open-Source PSCAD Grid-Following and Grid-Forming Inverters and A Benchmark for Zero-Inertia Power System Simulations,» 2021 IEEE Kansas Power and Energy Conference (KPEC), Manhattan, KS, USA, 2021, pp. 1-6, doi: 10.1109/KPEC51835.2021.9446243. keywords: {Computational modeling;System integration;Power system stability;Inverters;Stability analysis;Mathematical model;PSCAD;inverter-based resources;generic models;PSCAD;zero inertia;power system stability},

[5] Western Electricity Coordinating Council, “Model Specification of Droop-Controlled, Grid- Forming Inverters (REGFM_A1)”, USA, 2023.

[6] Du, Wei, Sebastian Achilles, Deepak Ramasubramanian, et al., 2024. Virtual Synchronous Machine Grid-Forming Inverter Model Specification (REGFM_B1). UNIFI-2024-6-1

[7] European Network of Transmission System Operators for electricity “Grid Forming capability of power park modules”